Abstract

Introduction

Discovery is a core practice within Customised Employment, used to identify the strengths, interests, and conditions for success of people with disability through qualitative, person-centred exploration rather than standardised assessment. Despite strong evidence that families influence employment outcomes, their role within Discovery remains informal, inconsistent, and largely untheorised.

Aim

This paper examines the role of families within Discovery and proposes a structured model for embedding family involvement as a core component of inclusive employment practice, with the Australian employment ecosystem as a reference point.

Methods

Drawing on the Equilibrium Systems Model of Employment (ESME), which conceptualises employment as an ecological system shaped by interactions among individuals, families, providers, employers, and policy environments, the paper integrates international literature with applied practice experience to develop the Family Discovery Model as a conceptual and practice-informed framework. The model is examined in relation to co-production theory, Customised Employment fidelity, and contemporary disability employment policy contexts.

Results

The Family Discovery Model positions families as system actors who contribute through narrative building, network mapping, and collaborative reflection. These functions strengthen employment planning, improve alignment between participant goals and service delivery, and enhance system coherence. Practice-based examples illustrate application across school-to-work transitions, movement from segregated employment, and pathway development for individuals with intellectual, developmental, and complex support needs.

Conclusion

Embedding families as co-producers within Discovery offers a practical and scalable mechanism for strengthening rehabilitation practice and advancing inclusive employment systems. By operationalising family involvement within a structured framework, the model supports improved employment outcomes, greater fidelity to Customised Employment principles, and stronger alignment with contemporary disability policy objectives.

1. Introduction

Employment outcomes for people with disability remain persistently poor despite decades of legislative reform, service innovation, and targeted investment. In Australia, initiatives such as the Disability Discrimination Act 1992, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), and successive iterations of Disability Employment Services were intended to improve access to open employment. However, employment rates for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities have remained largely unchanged since the mid-1990s (Mank & Grossi, 2013; Smith, 2023a). Internationally, similar patterns are evident, with substantial investment in vocational rehabilitation yielding uneven outcomes and limited systemic change (Butterworth et al., 2024). One underexamined contributor to this stagnation is the role of families. Families are often the most enduring influences across the life course, shaping expectations, advocacy, and access to social networks. Research consistently demonstrates that family expectations are among the strongest predictors of employment outcomes, particularly during school-to-work transition (Carter et al., 2012; Kramer et al., 2020). Higher expectations are associated with improved outcomes, while low expectations are linked to continued segregation and limited employment pathways (Test et al., 2009). Despite this influence, families are rarely embedded within formal employment practice and are typically engaged in informal or ad hoc ways rather than as structured contributors (Migliore et al., 2012). This paper advances an expanded conception of Discovery that systematically incorporates families as co-producers of employment knowledge. Within Customised Employment, Discovery refers to a structured, qualitative process through which practitioners develop a rich understanding of a person's interests, strengths, conditions for success, and support needs through observation, conversation, and engagement across everyday settings, rather than through standardised assessment or readiness testing. Drawing on the Equilibrium Systems Model of Employment (ESME), which conceptualises employment as an ecological system in which outcomes emerge through interactions among individuals, families, providers, employers, and policy environments (Smith, 2018, 2026), this paper positions families as system actors who actively shape employability over time. The Family Discovery Model is introduced as a structured, competency-based framework that enables meaningful family participation in Discovery while safeguarding participant agency, choice, and self-determination. From a rehabilitation science perspective, Family Discovery extends traditional vocational approaches by embedding relational and ecological dimensions within employment planning. Rather than focusing solely on individual capacity, the model aligns rehabilitation goals with family systems, community connections, and environmental supports, reflecting contemporary understandings of disability as an interaction between individual and context. The paper proceeds in four stages. It first reviews literature on family involvement in employment. It then outlines the Family Discovery Model and its theoretical grounding in ESME. Next, it examines application within policy and practice contexts, illustrated through practice examples. Finally, it proposes a research agenda and considers implications for policy, practice, and future scholarship, positioning Family Discovery as a systemic innovation capable of advancing inclusive employment reform.

2. Literature Review

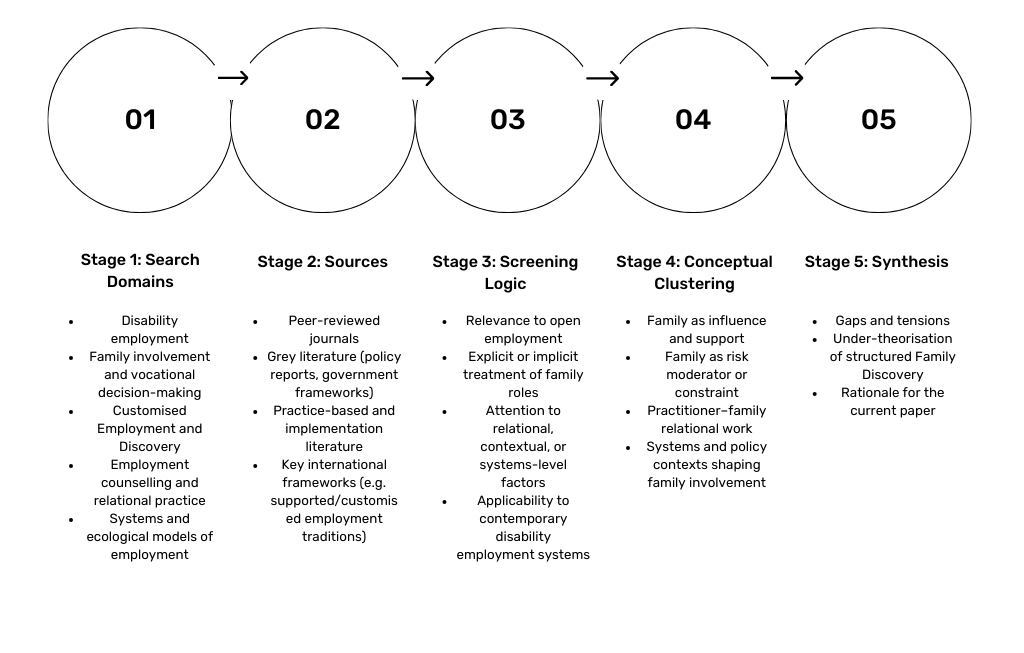

To provide transparency in how the literature informing this paper was identified and synthesised, a structured scoping and mapping process was used. Literature was sourced across peer-reviewed, policy, and practice-based domains relevant to disability employment, family involvement, and relational practice. Rather than aiming for exhaustive coverage, the review prioritised conceptual relevance to Family Discovery and open employment pathways. Figure 1 summarises the search domains, screening logic, and conceptual clustering used to inform the analysis. Systemic barriers continue to limit families' capacity to participate meaningfully in transition planning. Francis et al. (2022) identify time constraints, linguistic diversity, and unequal power dynamics in school-home relationships as persistent barriers, particularly for families from low-income and culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Longitudinal research supports these findings. Kirby (2016) demonstrated that parental expectations mediate the relationship between background characteristics and adult outcomes for autistic young people, with higher expectations associated with improved employment, independent living, and community participation. Systemic barriers continue to limit families' capacity to participate meaningfully in transition planning. Francis et al. (2022) identify time constraints, linguistic diversity, and unequal power dynamics in school-home relationships as persistent barriers, particularly for families from low-income and culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Longitudinal research supports these findings. Kirby (2016) demonstrated that parental expectations mediate the relationship between background characteristics and adult outcomes for autistic young people, with higher expectations associated with improved employment, independent living, and community participation.

The influence of families on employment outcomes is well established. Parents and carers often provide critical insight into an individual's interests, strengths, and support needs and play central roles in advocacy and service navigation during key transitions such as school-to-work and movement from segregated to open employment (Carter et al., 2012; Hetherington et al., 2010). Empirical studies consistently identify family expectations as a strong predictor of post-school outcomes. Carter et al. (2012) found that higher parental expectations were associated with improved employment outcomes, while Test et al. (2009) identified expectations as among the most robust predictors of successful transition. These findings highlight the dual role of families as potential facilitators of employment and, when unsupported, unintentional constraints on opportunity. Despite this influence, families remain marginal to formal employment practice. Migliore et al. (2012) found that family involvement was typically peripheral and inconsistently integrated into planning processes. This pattern is reflected in system-level evaluations. The Australian Government's mid-term review of Disability Employment Services reported substantial increases in caseloads without corresponding improvements in employment outcomes, alongside rising costs per placement. Participants and employers identified limited tailoring and weak engagement with natural supports, pointing to the absence of structured mechanisms for family involvement (Australian Government Department of Social Services [DSS], 2020). These findings align with broader co-production literature, which emphasises that meaningful service innovation occurs when service users and families are recognised as contributors to knowledge and outcomes rather than passive recipients of support (Bovaird, 2007). Customised Employment (CE) is an employment model that emerged in the early 2000s in response to persistent exclusion of people with significant and complex disabilities from competitive integrated employment. CE is designed to individualise the employment relationship through person-centred planning, negotiated job design, and alignment between individual strengths and employer needs, with Discovery serving as a foundational process (Callahan & Griffin, 2011; Griffin et al., 2007; Riesen et al., 2023). While CE represents a significant advance in inclusive practice, Discovery has largely remained a professionalised activity, with families rarely formalised as contributors despite their relational knowledge and long-term involvement. Efforts to strengthen family engagement have included initiatives such as the Family Employment Awareness Training (FEAT) program. Evaluations indicate that FEAT increases family knowledge, confidence, and engagement with employment systems (Francis et al., 2013; Grossi, 2014), with later studies reporting improved professional awareness of systemic barriers and family contributions (Francis et al., 2014; Gross et al., 2025). However, these initiatives primarily operate at the level of awareness-raising. Families remain positioned as recipients of information rather than active co-producers of employment planning. This reflects a broader gap in practice. While policy and research increasingly acknowledge the importance of family engagement, few models articulate how families can be systematically embedded within employment planning processes. As a result, family involvement remains consultative rather than collaborative, limiting its impact on employment outcomes (Grigal et al., 2019). The Family Discovery Model is proposed in response to this gap, providing a structured framework through which family knowledge, networks, and lived experience can be integrated as active components of Discovery rather than peripheral inputs.

3. Materials And Methods: The Family Discovery Model

The Family Discovery Model is grounded in the principles of Customised Employment and situated within the Equilibrium Systems Model of Employment. Customised Employment emphasises individualisation, person-centred practice, and the negotiated creation of employment opportunities, with Discovery used to identify strengths, interests, and support needs relevant to job development (Callahan & Griffin, 2011). In practice, however, Discovery has often been implemented as a provider-led activity shaped by professional judgement and system constraints. The Equilibrium Systems Model of Employment reframes this approach by conceptualising employment as an ecological system in which outcomes emerge through interactions among individuals, families, providers, employers, and policy environments (Smith, 2018, 2026). This perspective aligns with co-production theory, which emphasises that sustainable outcomes depend on the meaningful involvement of those who hold experiential and contextual knowledge (Bovaird, 2007; Needham & Carr, 2009). Within this system, families represent a critical but underutilised resource, offering continuity across life stages, detailed knowledge of the individual, and access to social networks beyond formal services. The Family Discovery Model formalises this contribution by positioning families as co-producers of employment knowledge rather than peripheral participants. The model is implemented within existing Customised Employment services as an extension of Discovery rather than as a standalone intervention. It is facilitated by trained employment practitioners, with families participating as structured contributors to knowledge generation rather than as service recipients or decision-makers. Implementation requires targeted training for practitioners and families, focusing on narrative development, network mapping, collaborative reflection, and ethical safeguards to protect participant agency. Integration within existing service systems is supported through alignment with established quality and fidelity frameworks, enabling family contributions to be documented and incorporated into routine employment planning without displacing professional responsibility for job negotiation and workplace design. Within the model, families contribute through three interrelated functions that extend Discovery beyond professionally mediated knowledge. First, families engage in narrative building, contributing longitudinal accounts of personal history, interests, routines, and responses to environments that may not be accessible through time-limited professional observation (Grigal et al., 2019). This narrative knowledge provides critical context for interpreting preferences and identifying conditions under which employment is likely to be sustainable. Second, families support network mapping by identifying social, community, and informal economic connections that can generate employment opportunities beyond provider-led or vacancy-driven pathways, expanding the range of negotiable employment possibilities (Callahan & Griffin, 2011). Third, families participate in collaborative reflection, a structured sense-making process in which participants, families, and practitioners align goals and co-produce employment strategies over time. This function requires explicit attention to participant autonomy, particularly where family expectations may unintentionally narrow choice or constrain vocational identity development (McConnell et al., 2019). The model incorporates safeguards to ensure that family involvement strengthens rather than undermines person-centred practice. Families contribute knowledge and networks, while responsibility for job negotiation and workplace design remains with trained practitioners. This division of roles preserves participant agency and aligns with international rights frameworks, including the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, 2006). Consistent with co-production literature, clarity of roles and structured collaboration are essential to ensuring that participation enhances outcomes (Needham & Carr, 2009). The model is supported by a structured training framework that equips families with the competencies required for meaningful participation. Aligned with the NDIS Participant Employment Strategy 2024-2026, the approach situates family involvement within broader employment systems, including Inclusive Employment Australia and reforms to Australian Disability Enterprises (NDIS, 2024; Grigal et al., 2019). Training emphasises person-centred practice, narrative development, and strengths identification (Carter et al., 2012; Grossi et al., 2018), alongside network mapping and collaborative engagement with providers and employers (Callahan & Griffin, 2011; McConnell et al., 2019). Learning is consolidated through the Family Discovery Action Plan, which integrates family-generated narratives, networks, and strategies into formal Discovery documentation. While detailed training materials are beyond the scope of this paper, the model is designed to function as an embedded component of high-fidelity Customised Employment practice. By integrating family-derived knowledge alongside professional assessment, Family Discovery strengthens the evidentiary basis for job development and supports shared ownership of outcomes.

4. Family Discovery in Policy and Systems Contexts

The Equilibrium Systems Model of Employment conceptualises disability employment as a dynamic system in which outcomes emerge through interactions among individuals, families, providers, employers, and policy environments (Smith, 2018, 2026). Although families have long been recognised as influential, they have typically remained peripheral to formal employment systems. The Family Discovery Model reframes this position by recognising families as active system actors whose contributions support continuity, stability, and more coherent employment planning. In doing so, employment pathways reflect not only professional assessment and participant aspirations but also the relational knowledge and social capital held by families. This framing aligns with international co-production literature, which emphasises that effective service systems emerge when users and families are embedded within design and delivery processes rather than consulted episodically (Bovaird, 2007). While this paper is grounded in employment systems characteristic of liberal welfare regimes such as Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom, where family involvement often compensates for fragmented service provision, the model does not presume universality and may require adaptation in social democratic contexts where the state assumes a more central coordinating role. Integrating families within ESME strengthens system functioning by broadening the knowledge base, mobilising natural supports beyond formal services, and reinforcing accountability through alignment with participant-defined goals. Through these mechanisms, Family Discovery contributes to the systemic balance central to ESME. The current Australian policy context provides a timely opportunity to embed this approach. The introduction of Inclusive Employment Australia from November 2025, alongside the NDIS Participant Employment Strategy 2024-2026, reflects renewed emphasis on early intervention, choice, and inclusive pathways (Department of Social Services, 2025; Services Australia, 2025). Together with reforms targeting Australian Disability Enterprises, these developments create conditions for innovation. Family Discovery offers a structured and fundable mechanism through which commitments to co-production can be operationalised, enabling families to participate as contributors to employment planning rather than passive consultees. Comparable patterns are evident internationally. In the United States, Discovery is widely used within Customised Employment but remains largely provider-led, with family involvement typically informal or inconsistent. Programs such as FEAT demonstrate the value of family engagement but stop short of embedding families as co-producers within Discovery (Grossi et al., 2014; Gross et al., 2025). In the United Kingdom, co-production is widely endorsed in principle, yet systematic mechanisms for family involvement remain limited. In this context, Australia is well positioned to lead internationally by formalising Family Discovery as a replicable model aligned with obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, 2006). The benefits of integrating Family Discovery operate across multiple levels. For individuals and families, employment planning becomes more responsive and relational. For providers, family involvement strengthens continuity, improves information flow, and supports fidelity to Customised Employment practice. At the system level, Family Discovery offers governments a practical mechanism for translating policy intent into measurable practice while leveraging natural supports to improve efficiency and sustainability. Important considerations remain. Families vary in capacity, resources, and cultural context, requiring approaches that are flexible and inclusive. Safeguards are essential to ensure that family involvement strengthens rather than constrains participant agency. Organisational and policy adjustments are also required, including workforce development, formal recognition of family roles, and aligned funding structures. Without these supports, family engagement risks remaining symbolic rather than substantive.

5. Research Agenda: Applied Evaluation Priorities

The integration of Family Discovery into Customised Employment requires systematic evaluation to support broader adoption. Evidence is needed to demonstrate effectiveness, implementation fidelity, and value for policy and practice, particularly given ongoing calls for evidence-informed approaches to competitive integrated employment for people with disability (Inge et al., 2018; Riesen et al., 2023). A focused research agenda is therefore required to clarify what should be measured and how findings can inform service development. Four evaluation domains are central. First, outcome evaluation should examine whether Family Discovery improves employment results compared with provider-led Discovery. Key indicators include participation rates, job attainment, retention at 13, 26, and 52 weeks, and measures of job quality such as satisfaction, stability, and progression, consistent with prior evaluations of Customised Employment outcomes (Callahan & Griffin, 2011; Luecking et al., 2006; Riesen et al., 2023). Evaluation should also consider whether family networks generate employment opportunities beyond those typically accessed through provider-led job development and whether these approaches reduce reliance on formal supports. Second, process evaluation is essential to assess implementation fidelity. This includes examining whether narrative building, network mapping, and collaborative reflection are applied as intended and whether family contributions are meaningfully integrated into planning. Provider capability to facilitate these processes while maintaining participant agency is critical, aligning with broader implementation science literature emphasising fidelity, workforce capability, and organisational readiness (Fixsen et al., 2005; Riesen et al., 2019). Existing quality frameworks, including Customised Employment Organisational Fidelity & Elevating Capacity Tool (CEOFECT) and the Customised Employment Quality Assurance Framework (CEQAF), offer a foundation for embedding family engagement indicators within routine quality assurance (Inge et al., 2018; Riesen et al., 2023a). Third, participant experience represents a core evaluation domain. Family involvement should enhance, rather than compromise, self-determination. Evaluation should assess whether participants feel supported in shaping goals, whether family input aligns with individual preferences, and whether decision-making remains person-centred, reflecting established self-determination and person-centred practice literature (Wehmeyer et al., 2011; Shogren et al., 2017). Tools such as the Discovery Experience Reflection Scale (DERS) provide structured mechanisms for capturing participant and family perspectives and monitoring experiential fidelity to person-centred Discovery. Finally, system-level evaluation should examine how effectively Family Discovery is embedded within organisational and policy contexts. This includes alignment with service guidelines, funding arrangements, and quality assurance processes, as well as the extent to which providers adopt the model as routine practice. Comparative and cost-benefit analyses will be important in establishing economic value and informing commissioning decisions, consistent with systems and co-production literature emphasising value creation and public accountability (Bovaird, 2007; Luecking, 2011). Methodologically, mixed-methods approaches are well suited to this agenda, combining quantitative outcome data with qualitative insights from participants, families, and practitioners (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). Participatory approaches, in which families and participants contribute to research design and interpretation, are consistent with the principles underpinning Family Discovery and strengthen the relevance and legitimacy of findings (Cargo & Mercer, 2008). Together, these approaches position Family Discovery as both a practice innovation and a mechanism for system learning, supporting continuous improvement and more inclusive employment systems.

6. Implications

The Family Discovery Model has important implications for policy, practice, and research. Its adoption requires more than incremental change, as it challenges how systems recognise families, how practitioners collaborate with them, and how evidence is generated to support innovation. By positioning families as active system actors, the model functions not only as a practice enhancement but as a mechanism for broader system reform. From a policy perspective, Family Discovery emerges at a timely moment. The alignment of the NDIS Participant Employment Strategy 2024-2026 with the introduction of Inclusive Employment Australia from November 2025 creates an opportunity to embed family contributions within national employment services. While co-production is frequently referenced in policy discourse, few systems have translated this principle into operational practice. Family Discovery provides a structured and replicable mechanism through which commitments to inclusion and choice can be enacted. For this potential to be realised, policy frameworks must formally recognise Family Discovery as a fundable activity. Without explicit guidance and resourcing, family involvement risks remaining inconsistent or symbolic. Recognition may occur through inclusion in service guidelines, training subsidies, or integration within quality and performance frameworks. Equity considerations are also essential, with approaches needing to be accessible, culturally responsive, and adaptable across socioeconomic and geographic contexts. Embedding Family Discovery within national frameworks further supports alignment with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. For providers and practitioners, the model requires a shift in both mindset and practice. Families are positioned not as peripheral stakeholders but as partners whose insights inform Discovery and job development. This requires professional capability in facilitation, collaborative planning, and boundary management, particularly when integrating family narratives and networks into employment planning. Organisational systems must also evolve to document family contributions and support consistent implementation. When implemented effectively, Family Discovery can strengthen understanding of participant strengths, expand employer networks, and improve job matching, while safeguards ensure that participant voice remains central. For researchers, Family Discovery highlights the need to examine how family engagement shapes employment pathways beyond traditional outcome measures. Future research should assess impacts on employment outcomes, fidelity, and participant experience using comparative and longitudinal designs. Participatory approaches may further strengthen the evidence base by ensuring findings remain grounded in lived experience and applicable across diverse contexts. Taken together, these implications position Family Discovery as both a practice innovation and a system-level reform. Its effectiveness depends on policy recognition, organisational readiness, and a robust evidence base. When these conditions are met, Family Discovery has the potential to reshape not only how Discovery is conducted, but how inclusive employment systems are designed, implemented, and sustained.

6.1. Limitations and Future Research

This paper is conceptual in nature and does not present primary empirical data. While the Family Discovery Model is informed by practice-based application, further research is required to examine its effectiveness across diverse contexts. Future studies should assess implementation fidelity, employment outcomes, and participant experience using comparative and longitudinal designs. Additional research is also needed to explore scalability, cultural applicability, and system-level impacts across different service environments.

7. Conclusion

Employment outcomes for people with disability remain persistently poor despite sustained policy reform and program investment. One enduring limitation has been the absence of structured mechanisms for incorporating family knowledge into employment planning, despite clear evidence of families' influence on expectations, decision-making, and access to opportunity. This paper has introduced the Family Discovery Model as a response to this gap, positioning families as system actors within the Equilibrium Systems Model of Employment. By formalising family contributions through narrative building, network mapping, and collaborative reflection, the model reframes Discovery as a co-produced process grounded in lived experience rather than a solely provider-led activity. Conceptually, the model operationalises ESME by strengthening alignment across individual, relational, organisational, and policy domains. Practically, it offers a scalable framework that is compatible with Customised Employment fidelity requirements, enhances job development through expanded social networks, and mobilises natural supports while maintaining safeguards for participant agency and choice. At the policy level, Family Discovery provides an applied mechanism for translating co-production from principle into routine practice. Its relevance to contemporary reform contexts, including the NDIS and Inclusive Employment Australia, highlights its potential contribution to more inclusive, accountable, and sustainable employment systems consistent with obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The research agenda outlined earlier provides a basis for evaluating these contributions across outcomes, fidelity, and system integration. Taken together, Family Discovery advances both the theory and practice of inclusive employment by embedding family knowledge within Discovery in a structured, ethical, and systemically coherent manner. The author declares no financial or commercial conflicts of interest related to this work. The conceptual frameworks discussed in this paper have been developed through academic research and professional practice. The analysis and interpretations presented are independent and grounded in existing literature and policy sources.

References

- Australian Government Department of Social Services. (2020). Mid-term review of the Disability Employment Services (DES) program.

- Australian Government Department of Social Services. (2025a). Inclusive Employment Australia Deed 2025-2030.

- Australian Government Department of Social Services. (2025b). Inclusive Employment Australia guidelines: Part A - Administrative requirements.

- Australian Government Department of Social Services. (2025c). Inclusive Employment Australia guidelines: Part B - Servicing requirements.

- Bovaird, T (2007). Beyond engagement and participation: User and community co-production of public services. Public Administration Review, 67.

- Brookfield, S. D (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher (2nd ed.

- Butterworth, J and Christensen, J and Timmons, J (2024). State of the science: Employment of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Boston: Institute for Community Inclusion..

- Callahan, M and Griffin, C (2011). Discovery: Charting the course to employment.

- Cargo, M and Mercer, S. L (2008). The value and challenges of participatory research: Strengthening its practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 29.

- Carter, E. W and Austin, D and Trainor, A. A (2012). Predictors of postschool employment outcomes for young adults with severe disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 23.

- Creswell, J. W and Plano Clark, V. L (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.

- Fixsen, D. L and Naoom, S. F and Blase, K. A and Friedman, R. M and Wallace, F (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature.

- Francis, G. L and Gross, J. M. S and Turnbull, A. P and Blue-Banning, M (2022). Barriers to family involvement in transition planning: A qualitative metasynthesis. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 45.

- Francis, G. L and Gross, J. M. S and Turnbull, A. P and Turnbull, R (2014). An exploratory investigation into family perspectives after participating in the Kansas Family Employment Awareness Training. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 37.

- Francis, G. L and Gross, J. M. S and Turnbull, A. P and Turnbull, R (2013). The Family Employment Awareness Training (FEAT) program: Building the capacity of families to improve employment outcomes. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 38.

- Griffin, C and Hammis, D and Geary, T (2007). The Job Developer's Handbook: Practical Tactics for Customised Employment.

- Grigal, M and Hart, D and Weir, C (2019). Post-secondary education and employment for students with intellectual disability: Current status and future directions. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 57.

- Gross, J. M. S and Francis, G. L and Choi, J. H and Stanley, J. L and Bowen, E (2025). Professionals need information too: Exploratory data from the Family Employment Awareness Training (FEAT) in Kansas. Inclusion, 13.

- Grossi, T and Bates, P and Hewitt, A (2014). The Kansas Family Employment Awareness Training (FEAT): Building capacity for employment through family training. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 11.

- Unknown (2010). The lived experiences of adolescents with disabilities and their parents in transition planning. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 25.

- Inge, K. J and Graham, C. W and Brooks-Lane, N and Wehman, P and Griffin, C (2018). Defining customized employment as an evidence-based practice: Results of a focus group study. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 48.

- Kirby, A. V (2016). Parent expectations mediate outcomes for young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46.

- Kramer, J. M and Coster, W and Kao, Y.-C and Snow, A and Orsmond, G and Cohn, E. S (2020). The role of parental expectations in predicting post-school outcomes for young adults with developmental disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50.

- Luecking, D. M and Gumpman, P and Saecker, L and Cihak, D (2006). Perceived quality of life changes of job seekers with significant disabilities who participated in a customized employment process. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 37.

- Mank, D and Grossi, T (2013). Employment outcomes for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: The enduring gap. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 38.

- McConnell, D and Martin, J and Hennessey, A (2019). Families, Disability, and Inclusive Employment: Rethinking Roles and Responsibilities. Disability & Society, 34.

- Migliore, A and Mank, D and Grossi, T and Rogan, P (2012). Integrated employment or sheltered workshops: Preferences of adults with intellectual disabilities, their families, and staff. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 37.

- National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). (2024). Participant Employment Strategy 2024-2026.

- Needham, C and Carr, S (2009). Co-production: An emerging evidence base for adult social care transformation.

- Riesen, T and Hall, S and Keeton, B and Snyder, A (2023a). Internal consistency of the customized employment discovery fidelity scale: A preliminary study. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin.

- Riesen, T and Snyder, A and Byers, R and Keeton, B and Inge, K (2023). An updated review of the customized employment literature. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 58.

- Riesen, T and Hall, S and Keeton, B and Jones, K (2019). Customized employment discovery fidelity: Developing consensus among experts. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 50.

- Schutz, M. A and Awsumb, J. M and Carter, E. W and Burgess, L and Schwartzman, B (2025). Connecting youth with significant disabilities to paid work: An innovative school-based intervention. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 63.

- Shogren, K. A and Dean, E. E and Griffin, C and Steveley, J and Sickles, R and Wehmeyer, M. L and Palmer, S. B (2017). Promoting change in employment supports: Impacts of a community-based change model. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 47.

- Smith, P (2018). A systems analysis of factors that lead to the successful employment of people with a disability (Doctoral dissertation, University of Sydney).

- Smith, P (2023a). Customised employment and the NDIS: A pathway for inclusive reform. Journal of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, 2.

- Smith, P (2023b). Reimagining disability employment: Frameworks, fidelity, and the future of customised work.

- Smith, P (2026). The Equilibrium Systems Model of Employment: A systemic framework for inclusive pathways.

- Test, D. W and Fowler, C. H and Kohler, P (2009). Evidence-based predictors of improved postschool outcomes for students with disabilities. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 32.

- United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

- University of Kansas. (2025). Family Employment Awareness Training (FEAT) research brief. Kansas University Center on Developmental Disabilities..

- Wehmeyer, M. L and Shogren, K. A and Little, T. D and Lopez, S. J (2011). Development of self-determination through the life course. Springer.